Teaching Your Child Hindi? Do Yourself a Favor — Ditch the Hindi Script (for now)

Why the script-first approach makes the bilingual process harder on you and your child.

Most people who start teaching their child Hindi, teach script first and the actual language second. This is a BIG mistake which can lead to a million different issues down the line. For one, Devanagari is extremely different from the English script. It can be confusing and intimidating for your child (this is especially the case if they don’t know how to speak or understand it yet). This confusion can lead to embarrassment, and general disliking of Hindi, which makes them want to use it less.

Just to illustrate the point, read the below poem.

Regardez les branches

Comme elles sont blanches,

Il neige des fleurs.

Riant de la pluie

Le soleil essuie

les saules en pleurs.

Unless you speak French, the poem extract means nothing to you. You could probably sound out the letters and read it out loud – but in reality, it is just jibberish.

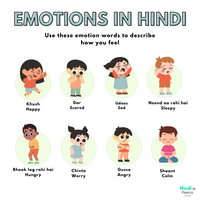

This is what it is like if your kids do not understand or speak Hindi, but are taught the alphabet first. They can read the alphabet. Use the matras. But it means nothing if they cannot answer “aapka naam kya hai.”

As an Indian who grew up in the US, my siblings and I started learning Hindi through conversation. We would talk to my grandmother in Hindi, watch movies, and learn new words by asking questions and actively using them. I only learnt the alphabet when I was older, when I understood a good chunk of what I was reading and writing.

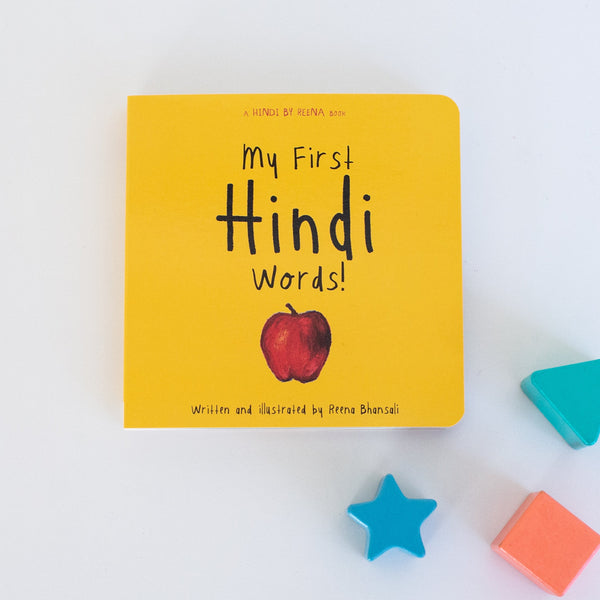

So many apps and Hindi materials out there start by showing your child the alphabet. They want them to remember the letters, trace them and learn 3-4 words that start with that letter. Does this help your child learn Hindi now? Does it get them closer to speaking with their family in Hindi? Sadly, no.

When I started teaching – with other Hindi teaching schools – they believed the alphabet was king. I would say “Ka” and the class would drolly repeat after me and I would provide some associated words like “kabutar” and “kachua.”